When Brett Cotten first poured the brown gloop into baking trays in his kitchen lab, the entrepreneur admits that the results looked rather like a flapjack. Some refinements of the supramolecular chemistry and £4m of investment later, and now Arda Biomaterials, his Bermondsey-based company, is producing a strong and supple kind of leather-like material that has been successfully tested in the making of bags and wallets.

The Bio-Textiles Revolutionising Fashion

13th January 2026

With their surprising plant-based and even bacterial origins, pioneering bio-textiles are being woven into the fabric landscape.

What’s curious is what it’s made from: proteins derived from brewers’ spent grain (BSG). That’s the primary waste material from beer-making, which brewers typically pay to have taken away, to be used for cattle feed or, worse, dumped in landfill. But this is not just about making good from waste: critically, Arda’s product is a replacement for both ‘pleather’ — the petrochemical-based faux leather — and the real thing, with its often dubious animal welfare record. There’s so much BSG around, Cotten reckons just 10 per cent of it could meet global leather demand.

“The look and feel of our material are important, of course, but talk to fashion brands and they do want something with a lower impact — and you find that often half of their footprint comes just from their choice of materials,” says Cotten. “Clearly, the public is increasingly thinking more about the issues around textile production too.”

Indeed, Arda is far from alone in exploring the potential to create textiles from the unexpected. Scientists and start-ups, such as Algiknit or Modern Meadow have, over the last decade, explored the repurposing of plant materials. For example, Fluff Stuff, which was launched three years ago, is a textile filling for quilted puffa-style clothing derived from broadleaf cattail plants, which also happens to absorb 66 per cent less water than down and dries twice as fast as traditional duck down. But they have also experimented with many types of feedstocks — mycelium, mushroom spores, yeast, orange fibres, agricultural waste, seaweed, milk and even bacteria among them — with a view to pioneering entirely new textiles from scratch.

“Textiles are fundamentally polymers, and, in principle, those polymers could be derived from all sorts of biomasses with a carbon structure as their backbone, so there’s a lot of opportunity here,” explains Rosa Arrigo, associate professor in inorganic chemistry at the University of Salford. “We need to make the likes of nylon and polyester sustainable, and they could be developed from bio-based resources instead of petrochemicals. And, given time and resources, completely new kinds of textiles could also be created.”

Take, for example, the ground-breaking raincoat made using a carbon-negative, plastic-like material created from algae by the US industrial designer and researcher Charlotte McCurdy — a bio-textile that would later be used for a one-off Phillip Lim dress, complete with algae-based sequins. She’s now working on developing bio-textiles capable of replicating the elastic properties of fossil fuel-based fabrics such as Spandex. McCurdy also reckons bio-textiles are about to really resonate. “I think we’re seeing the same shift for bio-textiles as happened with organic food,” she argues. “That was originally seen from an environmental point of view, but as soon as the more personal health perspective was pushed, the market exploded. And with bio-textiles we’ll see the same shift from the environment to health, regarding the impact of micro-plastics and toxins from clothing, which we’re more knowledgeable about now.”

McCurdy also predicts that the fashion industry is likely to take more interest in bio-textiles too, if only as a way of shifting how clothing is currently framed in the context of sustainability. Away, she says, from the commonplace green thinking that posits clothing as intrinsically environmentally harmful and even trivial, the only solution being to consume less of it, and towards a mindset that can again embrace clothing as one aspect of, as she puts it, “living positively."

Bio-design is also filtering into the things we put in our homes. Pioneering Danish designer Jonas Edvard has been working with mushroom mycelium to make experimental textiles since 2012, combining different plant-based materials for their specific qualities and resulting in a kind of fluffy skin that is modified to produce either a hard or flexible structure. So far he’s turned this bio-material into the likes of rough-and-ready, grow-your-own lampshades and chairs.

Getting there won’t be easy, however. We may, as some suggest, be gradually moving towards a more nature-driven approach to design, in which we’re inspired by the properties and behaviour of organisms. But bio-textiles remain both a niche industry, mostly still in the research phase, and face multiple challenges — not least, Arrigo suggests, funding and a lack of coordination between science and the needs of industry.

Brett Cotten has reservations too: “When you get into the weeds, you find problems with the feedstock – ensuring supply and that it is consistent and processed consistently, for example – or with performance or pricing,” he says. “And to reach the public with these textiles, you need massive scaleability and a guaranteed quality because no fashion brand will compromise on that, and affordability. So I think in the end there will only be a few great winners out of the hundreds [of experiments]."

Then, argues Assunta Marrocchi, associate professor of biotechnology at the University of Perugia, Italy, where she co-heads the Polymeer Project to develop a BSG-derived bio-plastic, there is the challenge of image. Not least, this includes the need to overcome the perceived “yuck factor” in wearing a garment derived from many of the proposed feedstocks. “The problem is persuading people to accept bio-textiles,” she says. “They hear ‘bio-based’ and immediately think ‘bio-degradable’ and then just ‘degradable.’ They assume these textiles are not long-lasting. So there’s education to be done."

These many complexities are why, to date, bio-textiles have typically been made for products at the luxury end of the market, which has been more able than the mass-market to trumpet sustainability as a sales pitch, and produced more as talking points than commercial ones. Over recent years, for example, Italian luxury goods company Loro Piana has launched a limited-edition £3,000 blazer made from a silk-like yarn derived from lotus leaves.

Slowly though, these new textiles are being embraced less for being an alternative to some more commonplace, environmentally unsound textile, and more for their own particular benefits. Sportswear company Sundried, for example, uses a fabric derived in part from coffee grounds, for its advanced sweat-wicking and UV protection properties, with Pangaia making some of its activewear from fibres derived from castor oil or corn. “We’re working closely with innovators worldwide to bring next-generation materials into wearable, everyday pieces, showing both the industry and customers that these better solutions exist today,” as the brand’s chief impact officer, Maria Srivastava, has it.

Meanwhile, German company Qmilk creates a fabric out of casein, a protein derived from milk deemed unfit for human consumption, which is used by Vaude, the performance clothing brand. Qmilk has the tensile strength of wool and can be blended with other fabrics, and is also hypoallergenic, anti-microbial, moisture-wicking, flame-retardant and temperature-regulating: ideal for hospital bedding, for example.

“Fashion often resonates with a wider group of people, but it’s in the specialist application that bio-textiles will pay off; for sport, for automotive upholstery, and so on,” says Marrocchi. “Unfortunately, these specialist industries are not very good at communications, certainly relative to fashion. These bio-textiles will eventually break through, but we’re not there yet."

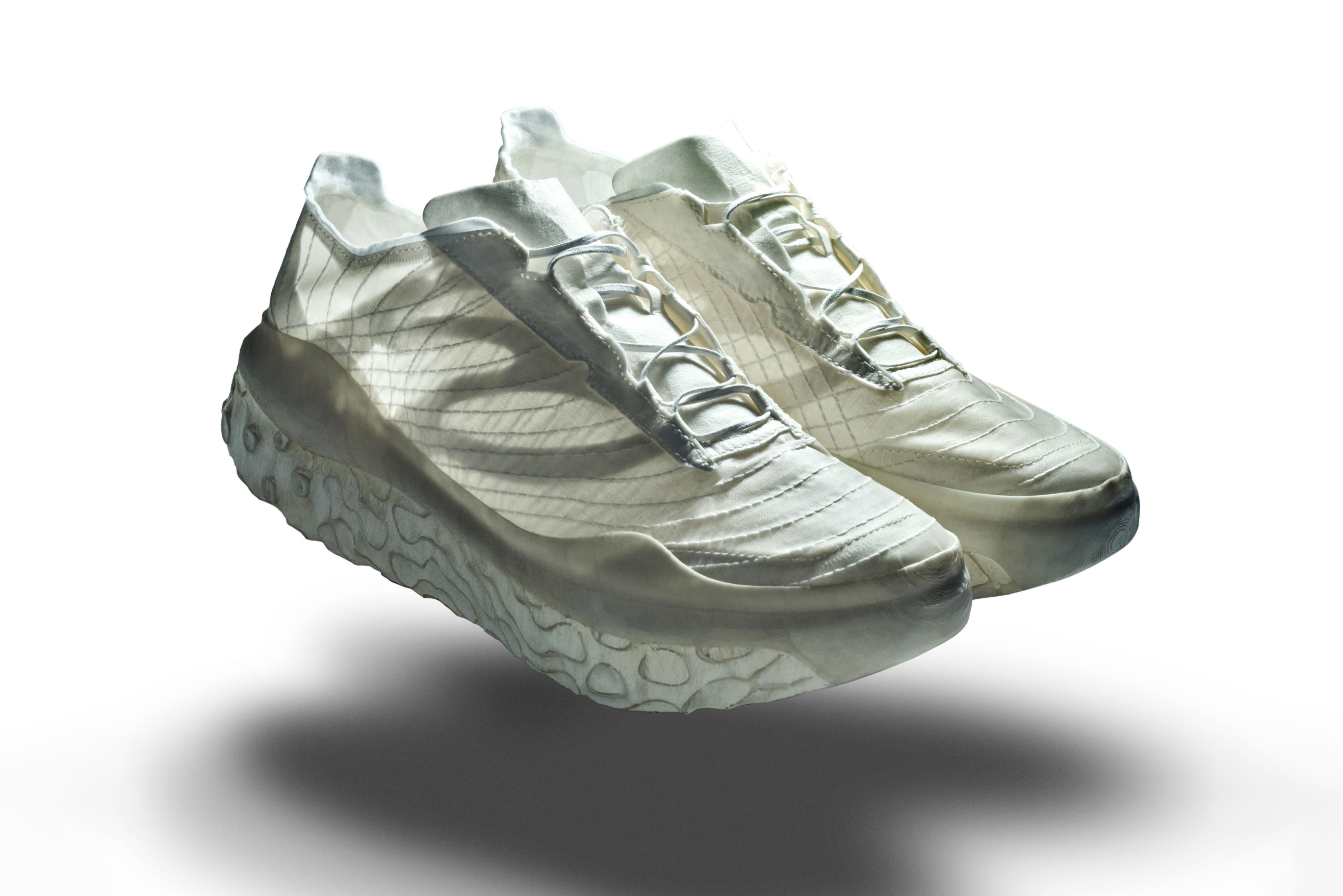

Indeed, to get there, perhaps we need to frame these new bio-textiles in a new way. Jen Keane is co-founder of Modern Synthesis, a London-based developer of a form of “microbial weaving” that uses a specific strain of bacterial nanocellulose to create a hybrid material that is grown rather than spun or woven, but strong and lightweight enough to be used for shoes. Keane argues that we need to stop seeing bio-textiles as a way of displacing those derived from petro-chemicals and value them for their own potential. “It’s hard for people to imagine what these new materials can do when we’re so used to the ones we’re familiar with and understand,” she says. “But we are trying to do something new here. And, yes, the new ones are going to feel and look different. We shouldn’t just be trying to replicate those materials that have been around for centuries, but also celebrate the novelty of the new ones. And there are so many of these all at the cusp of launching now, just at the final push. But we’re close, and it’s happening."