Most women’s jewellery boxes today contain similar types of pieces. Necklaces, especially non-traditional pearls — tick. A showy cocktail ring — tick. Small chains, rings and earrings to stack — tick, tick, tick. But brooches? If you do have one languishing in a corner, it’s probably an inheritance that you haven’t worn in years. You may even have thought about having it remade as something different. If you have, stop right there.

Brooches make a Glittering Comeback

17th December 2023

Shedding their frumpy reputation, brooches are making a comeback as women and men alike embrace the glittering trend.

In line with an immutable law that states whatever is most out will become the next big thing, the brooch is surging back. In many cases, it is literally big — the star of many a current red-carpet outfit. And that’s just the men. As they embrace the freedom to wear jewels, men are learning what women who enjoy tailoring have long known: nothing looks better on a sharply cut tuxedo lapel than a statement brooch (or pin, which sounds more unisex) in diamonds or gold.

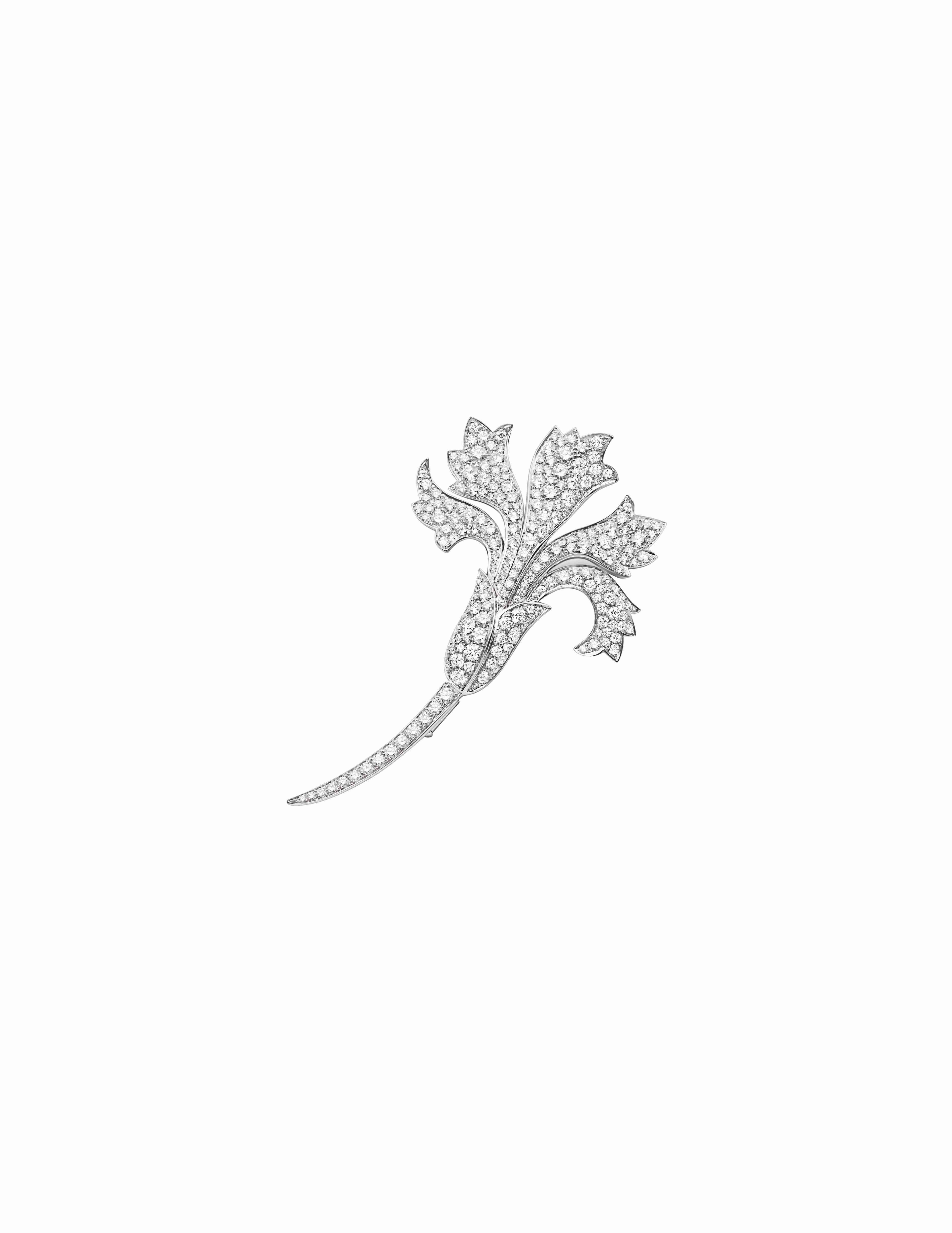

Venerable Paris jeweller Chaumet is almost as well known for brooches as for tiaras. CEO Jean-Marc Mansvelt — a keen pin-wearer — gives the historical context. “Jewellery for men used to be taboo yet men were the first to adorn themselves as a sign of power and virility — think of kings and maharajahs,” he says.

“Later, industrial society gave working men power, with only useful jewellery allowed: watches, wedding rings or buttons. Anything else was a sign of idleness. Yet in today’s more fluid world, a new model is being disseminated by actors, artists and singers who wear flamboyant jewellery, opening the door to all men. A brooch is an object of distinction, both important and discreet, which allows everyone to express themselves.”

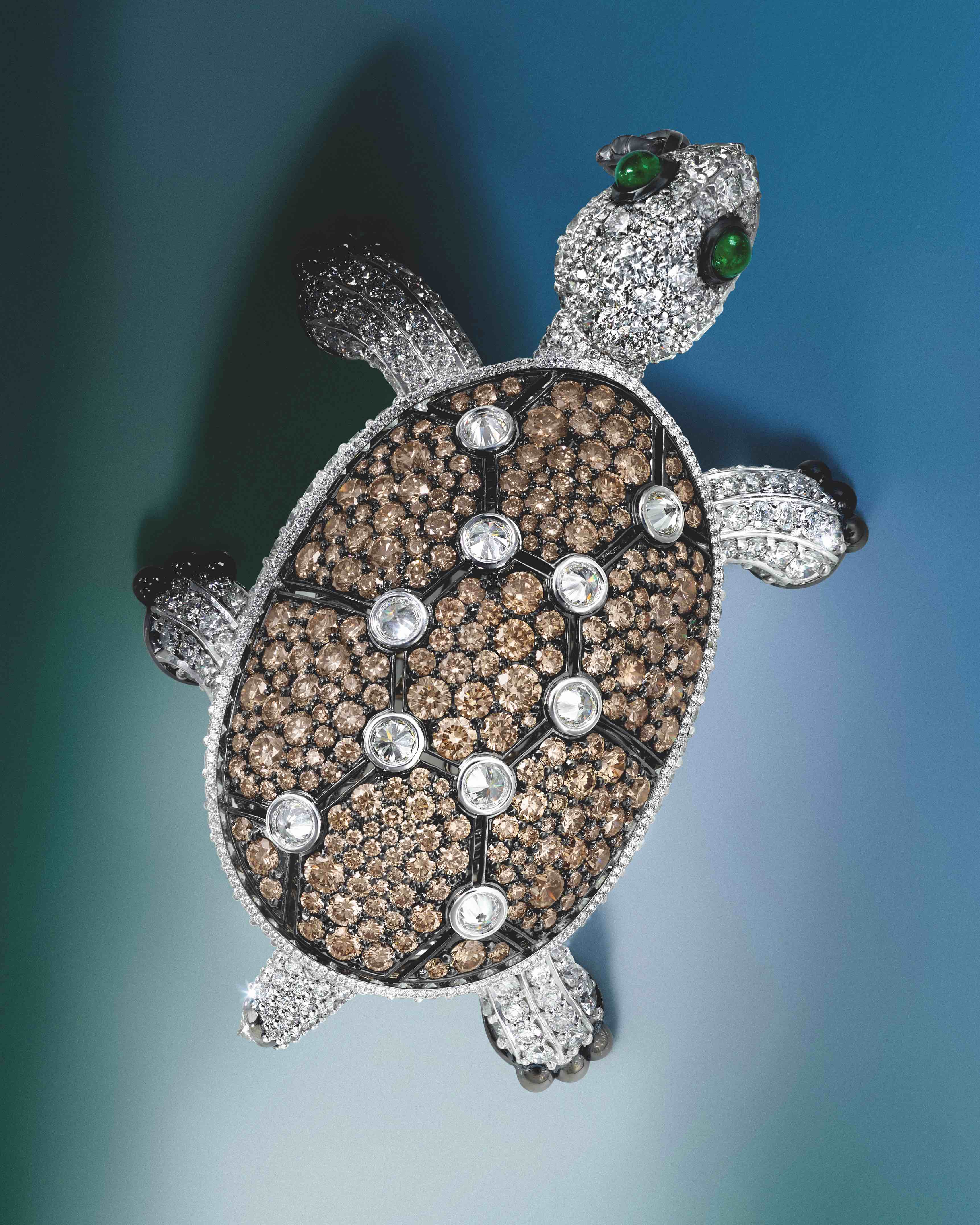

This has created a shift in design emphasis to bolder, less dainty pieces, even if some themes are more feminine by association. Chopard has seen a marked increase in brooch sales, particularly to men happy to wear an XL butterfly or rose, or a swagged elephant-head design. Graff has added to its roster of flowers and butterflies with a unique, beautifully worked tortoise brooch. Crafted in cognac and white diamonds with emerald eyes and articulated legs set en tremblant, it is cute enough for woman-appeal but tough enough for man-wear.

The same goes for Tiffany’s Schlumberger-inspired jellyfish — elegant but deadly in sapphires and moonstones. Boodles takes a graphic route for two abstract, Art Deco-inspired brooches in engraved gold, diamonds and mother-of-pearl, each centred with a major gemstone and added to the high jewellery collection in response to demand.

And perhaps it is no coincidence that two swagged and tasselled crescent brooches from Harry Winston’s new Royal Adornments collection are named The King.

Of course, it is women who have traditionally owned brooch-wearing and we do not take kindly to being usurped. Yet it is we who have also neglected these jewels. Brooches have existed, originally in functional, clothes-fastening form, since prehistoric times, becoming a decorative female adornment by the 18th century.

By the early 20th century, explains Mansvelt, “they perfectly matched the needs of modern women’s more relaxed dress style — elegant, transformable and wearable. For decades they were the finishing touch, conveying a message and asserting a style, reaching a zenith in the 1980s with supersized brooches from couturiers such as Yves Saint Laurent and Thierry Mugler.”

Such pride invariably comes before a fall and the brooch’s loss of status was spectacular. By the 1990s, Mansvelt continues, “it was associated with granny’s wardrobe” — and not in a good, vintage way — until a couple of years ago. If men led the new charge, women who live in the glare of Insta and TikTok — from stage performers to influencers — were always going to go bigger and better. As 1980s style returned, so too did the gilt costume-jewellery style of couture brooches, with Schiaparelli, designed by Daniel Roseberry, and Goossens, owned by Chanel, the current leaders.

Large-sized haute joaillerie is an expensive challenge but modern materials ride to the rescue. The number of designers using notoriously hard-to-work titanium is rising fast. It is four times lighter than gold but three times as strong and is favoured by masters including Wallace Chan, Cindy Chao and Anna Hu, who also have access to extraordinary gems and for whom brooches have never lost their lustre.

Christie’s in London recently held Europe’s most extensive exhibition of Chan’s work, which also features his own jewellery inventions such as fluid-looking porcelain or a carved gemstone cut that gives multiple reflections. Chao’s unique, yearly butterfly brooches, with gems set in titanium so fretted that light pours in from both sides, have a waiting list of collectors before they are even designed. Hu’s repertoire of butterflies, orchids and lilies, also involving aluminium, seashells and carved hardstones, is bringing these ideas to a new generation.

Even houses using more conventional materials now create bolder brooches. The classic themes of flora and fauna are becoming upscaled and slightly twisted. Bulgari’s signature is exuberant colour, and brooches from the flamboyant Mediterranea collection feature supersized fantasy florals built around a classic central gem. Van Cleef & Arpels has always put femininity front and centre, and is unwavering in its support for brooches. This can be seen from the multicoloured marvels of its Grand Tour high-jewellery collection to its superficially sweet, cartoonish fine-jewellery animals in hardstone, mother-of-pearl and gold perlée, also spotted on male lapels.

Not all past brooches were modest and genteel. One of the most startling pieces in the V&A’s current Chanel exhibition is the Comète brooch from Mademoiselle’s only high jewellery collection, created in 1932. She was loaned diamonds by the International Diamond Corporation to promote the stones, many of which were returned and the pieces broken up. Its size and proportions are totally contemporary looking, and it inspires some of Chanel’s current brooches.

For those looking for inspiration, auctions are great sources of bold designs. Demonstrating increased demand for the item, Bonhams’ autumn London Jewels sale included an impressive range, from a Tiffany’s 1960s Schlumberger-designed, 9.2-cm-long peridot and diamond seahorse to an 1860s his ‘n’ hers pair of substantial turtle brooches based on carved garnets to a jokey Boucheron dog, in gold en tremblant with gas-tube legs, neck and tail, once owned by actress Jean Simmons. Or why not rework that long-spurned heirloom — into a bigger and better brooch?