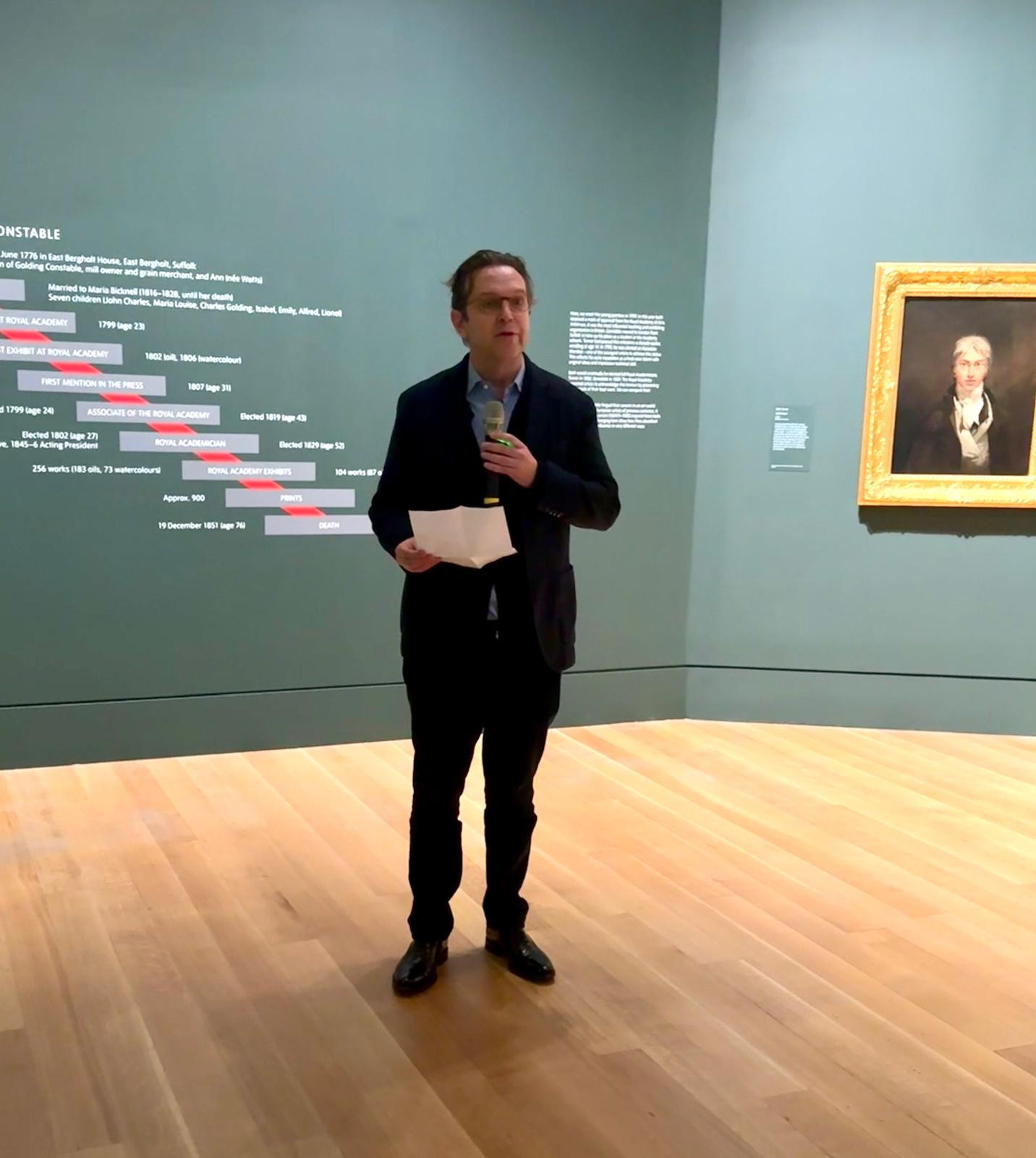

Art connoisseurs descended upon Tate Britain this week as it opened the doors to its new exhibition, Turner & Constable Rivals and Originals. In what Senior Curator of Historic British Art at Tate, and curator of the exhibition, Dr Amy Concannon describes as the “curatorial challenge of her career”, the exhibition seeks to give visitors the rare, “once in a generation” opportunity to view Turner and Constable’s work from start to finish, “side by side, but also distinctly”.

Inside Tate Britain Turner and Constable Exhibition

27th November 2025

This week one of most fascinating artistic rivalries has come under the spotlight with the opening of the magnificent Tate Britain Turner and Constable exhibition. Marking the 250th anniversary of their births, this thrilling exhibition positions the two artists head-to-head against the competitive backdrop of 19th-century landscape painting and sheds new light on the driving force behind their respective success and evolving styles. Lisa Barnard and Emily Harvey compare and contrast

Although born within a year of one another, according to Concannon, Turner and Constable “looked at the same world in such a radically different manner”. Despite focusing on landscape as their subject of choice, they came from two very different viewpoints. As Constable’s extensive catalogue shows, he chose Suffolk as his muse, earning himself the title of “quite a homeboy” — possibly 18th-century code for unworldly? Turner, on the other hand, as Concannon details, needed to venture abroad, “using sketch books as a way to capture what he was experiencing and turning it into something bigger and more imaginative in the studio”.

The exhibition superbly unpicks the rivalry between the two with clarity and nuance. It seems, perhaps, that the rivalry was rather one-sided. After all, it was Constable who labelled Turner “he who would Lord over all” and who used his position on the hanging committee at the RA to give his artwork prime position in the exhibition — slap bang between two of Turner’s paintings. Clearly, he invited the comparison by committing what Concannon dubs a “curatorial faux pas”.

Visitors of the exhibition are first met with the artists’ portraits, accompanied by their respective diploma pieces — the very works they each selected to represent their art in the Royal Academy collection. Turner’s is a sublime scene aggrandising British landscape, medieval history, and the raw power of the Welsh mountains. Whereas Constable’s is more of a commentary on the productivity, pastoral bliss, and harmonious microcosm that is, of course, Suffolk. Visitors are also shown the artists’ respective paraphernalia — be it Constable’s foldable chair he took out into the countryside, or the paint box and brushes they used.

But it’s certainly understandable why Constable would want to paint himself in the same league as Turner. Turner, of course, is viewed “as an innovator” and “pre-eminent in British art history”, according to Tate Britain Director, Alex Farquarson. It’s for this reason that Tate named its most famous accolade, the Turner Prize, after him.

In what can only be described as a triumph for Tate Britain, a highlight of the exhibition is the featuring of one of Turner’s most critiqued works — Juliet and her Nurse — which hasn’t been shown in public since 1836. At the time, it sent the art press into a tailspin as they couldn’t gauge what time of day it was, nor the grouping in the bottom corner. Most notably of all, though, they simply could not get on board with shifting Shakespeare’s narrative. “Turner gave Juliet a holiday”, Concannon laughs, as she was famously from Verona, not Venice.

What’s clear as you make your way through the various rooms is that both artists became progressively bolder throughout their careers. After ascending into the Royal Academy, Constable appeared to pay less and less attention to what people thought of his art. His transition from smaller canvases to six-footers meant people began to view him in the same league as his counterpart. Turner also took great delight in teasing his critics who disliked his “overuse” of yellow, saying that no one else could use the colour as he had it all to himself.

The show concludes with a short film featuring Bridget Riley, Frank Bowling, Emma Stibbon and George Shaw, each reflecting on Turner and Constable’s influence today. It’s a fitting reminder that whilst the two painters may have been considered rivals, the sustained and at times silent competition between the two became an underlying motivator for their success. Driving both artists to create a combined legacy that continues to shape how we interpret landscape painting today.