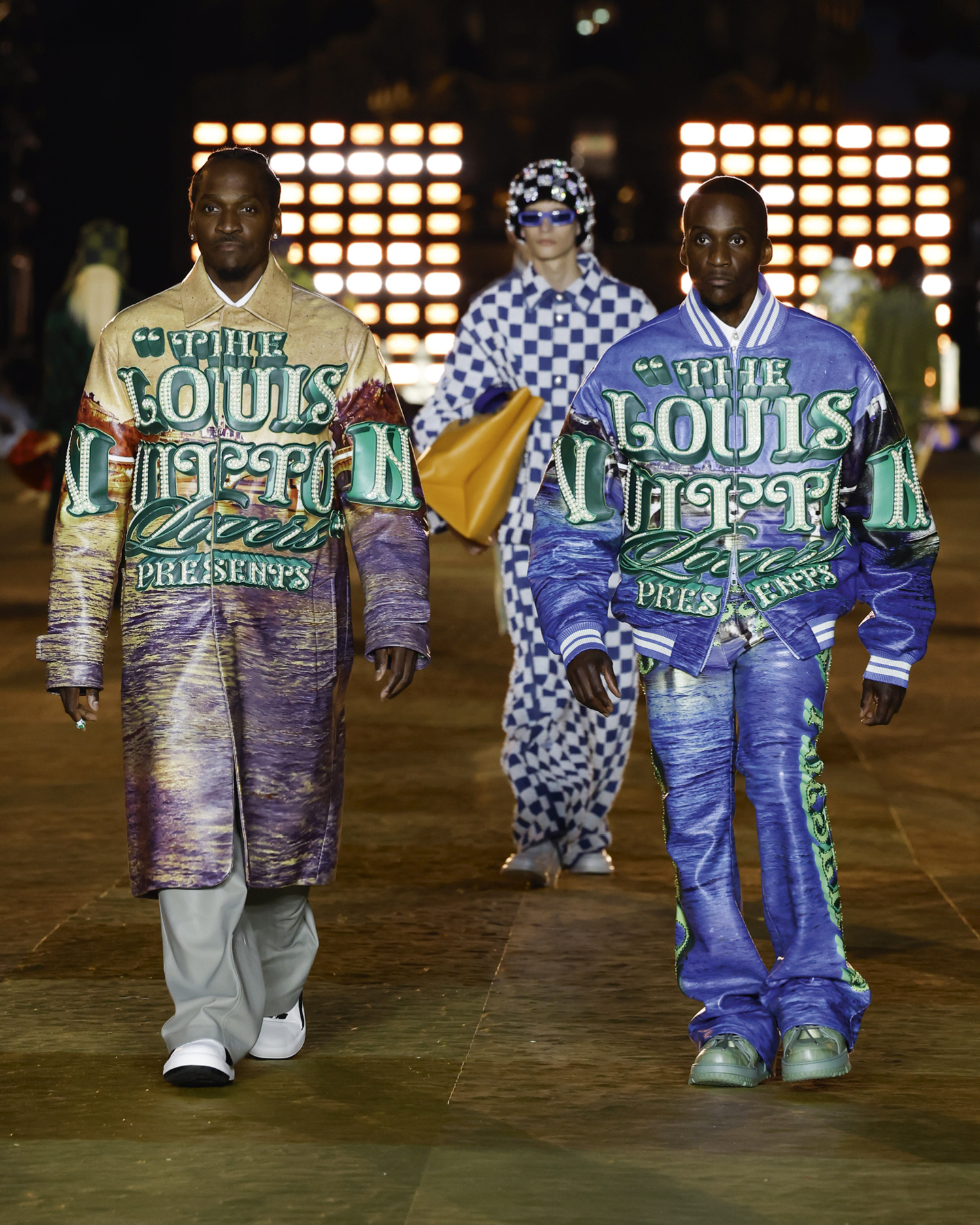

Even by the standards of a Paris runway show, Pharrell Willams' Louis Vuitton debut was pretty spectacular. The Pont Neuf in its entirety was paved with gold (or so it seemed) and colonised by a vast army of models and celebrities including Beyoncé, Jared Leto, Kim Kardashian, Lewis Hamilton, Rihanna and Lenny Kravitz. “The Louis Vuitton Spring-Summer 2024 Men’s Collection orbits the sun,” said the publicity, as if the point needed labouring. The reason for this hype and razzmatazz? This was the hotly awaited first collection from Pharrell Williams, who in February this year became Louis Vuitton’s creative director — an unexpected choice.

Pharrell Williams' Louis Vuitton Debut

9th October 2023

Fashion brands are appointing music stars and celebrities are starting their own labels. Join us as we check out Pharrell Willams' Louis Vuitton debut as Creative Director along with other creative crossovers that benefit all sides.

The first of Pharrell Williams' Louis Vuitton collection

This first collection made numerous references to Williams’s personal aesthetic, blending it with classic Louis Vuitton motifs. An exaggerated version of the maison’s Damier pattern, for instance, appeared on quilted denim jackets, full-length trench coats, leather motorbike jackets, baggy trousers and rugby shirts in navy, bright yellow and a rich burgundy. Multicultural musical performances closed the show, complete with the Voices of Fire gospel choir and a local Parisian choir, plus an orchestra led by pianist Lang Lang.

Williams has created fashion ranges before, of course, such as Billionaire Boys Club, but he’s best known as a multi-award-winning record producer, rapper, singer, songwriter. (Now that I’ve mentioned it, I defy you to get his 2013 hit “Happy” out of your mind.)

But according to Louis Vuitton, he’s also “a visionary whose creative universes expand from music to art, and to fashion — establishing himself as a cultural global icon over the past 20 years. The way in which he breaks boundaries across the various worlds he explores, aligns with Louis Vuitton’s status as a Cultural Maison, reinforcing its values of innovation, pioneer spirit, and entrepreneurship.”

Publicity aside, the appointment certainly seems to be a shrewd move in business terms. The financial markets were noticeably impressed, pushing Louis Vuitton’s stock price up 2.6% shortly after the announcement, to a high of €830.

And the brand isn’t alone in its unusual choice of creative director. Nigo was recently appointed artistic director of Louis Vuitton’s LVMH stablemate Kenzo. Although he launched his first independent fashion label in 1993, he’s better known as a music producer and DJ, and only staged his first fashion show very recently. Tomoaki Nagao, to give him his full name, has collaborated with musical talent including The Neptunes, Kid Cudi and Tyler, The Creator. He compared his most recent menswear collection with the Beatles’ seminal White Album to emphasise its variety and sense of experimentation.

Part of the reason for this trend is a change in the way that creative directors are viewed. “Historically, the creative director’s role was much more internally focused, product-oriented, and concerned with serving as a conduit between various teams, including design, marketing, management, and production, to ensure a shared vision,” says Andrew Groves, professor of fashion design at the University of Westminster.

The globalisation of luxury brands also plays a role, says Groves. “Now that the product is produced and sold globally, they need people who can communicate globally with a variety of audiences, including fashion enthusiasts, airport luxury consumers, and people buying perfume at Superdrug. It makes sense for brands to hire celebrities who have already cultivated global audiences, and tap into their markets.”

Tom Bourlet, who runs global marketing conference TIO, says: “The growth of influencer marketing has certainly seen it increase, with many big brands opting for a big-name profile over someone with more conventional work experience. The celebrity’s following offers them an opportunity to be seen by a large audience.”

Consumers are increasingly sceptical of social media influencers who appear to love any brand that is willing to pay them. “However,” points out Bourlet, “if the celebrity is working for the brand, then they may make regular Instagram stories and posts about their role, how they’re getting on and a new launch which they’re excited about.”

According to Groves, Kate Moss’s range for Topshop worked, for instance, because she clearly had the role of stylist. “She was your best friend, enabling you to wear the clothes she would wear to Glastonbury or out clubbing,” he says. “It’s less convincing when we are led to believe that the celebrities are creative directors in charge of range planning, tech drawings, fabric sampling and liaising with factories in Portugal. When the public believes that the creative director exemplifies the lifestyle they are selling, such as Phoebe Philo, Donna Karan and Miuccia Prada, then that can lead to a brand resonating with a consumer in a profoundly authentic manner.”

Pharrell Williams isn’t the only musician to move into fashion recently. Guy Berryman, the Coldplay bassist, has also launched his own clothing line. “Applied Art Forms was born through a desire to re-engage with my engineering and architecture background,” he explains. “I’ve always been a design-led person and a collector of utility, military and workwear garments. The label allows me a vehicle to express myself through physical creations, which I felt was something I couldn’t abandon after focusing the past 25 years on creating music. All of the Applied Art Forms garments are derived and inspired from my archive pieces and focus on timeless design and longevity — with updated, modern silhouettes.”

When Victoria Beckham launched her fashion label, some in the industry were critical about the idea that being a former girl-band member and the wife of a footballer was apparently a better route into high fashion design than years spent at fashion college and serving apprenticeships. Similar objections have been raised in the case of Williams’s appointment.

Is it about creativity — or simply about publicity and marketing? Certainly, according to research by WeArisma, an influencer marketing effectiveness provider, the announcement dominated social media conversations about the brand in the days following it. Over 80% of interactions mentioned Pharrell, while references to Louis Vuitton grew by 60% and its media value increased by 114%.

In some ways these appointments are part of a natural progression. For many years creative directors and designers have become celebrities — think Coco Chanel or Hubert de Givenchy — and have exploited their fame to market their brands and collections. Nigo and Williams have simply earned their celebrity before taking up the role. Similarly, celebrity endorsements have played a role in high-end fashion for decades and, more recently, famous names such as Reese Witherspoon and Sarah Jessica Parker have launched their own, eponymous labels, albeit with varying degrees of success. Taking a well-established, highly respected label and marrying it with a celebrity whose own brand is also A-rated is an obvious piece of synergy.

Creative directors and high-profile designers have long had muses who have enjoyed almost equal standing, such as Isabella Blow and Alexander McQueen or Jean Paul Gaultier and Madonna.

More recently, Harry Styles and Gucci have launched a creative collaboration that goes beyond simple celebrity endorsement. The Gucci HA HA HA campaign is based on the friendship between the singer-songwriter and actor and Gucci’s creative director Alessandro Michele, says the brand.

There are, though, risks for brands recruiting celebrity creative directors. Adidas was recently forced to end its relationship with the rapper formerly known as Kanye West after he made antisemitic remarks. The company’s inability to sell the footwear that a disgraced West had created for it has led to multi-million-dollar losses.

There are other risks, according to Jamie Ray, co-founder of Buttermilk, a global influencer marketing agency. “At times it can feel like faux entrepreneurship,” he points out. “How much does that celebrity really know about the industry? Do they have the technical skills or expertise to help run a fashion house? To minimise the risk of negative publicity, it’s important to ensure the brand-to-celebrity fit is authentic from a creative perspective.”

Luxury fashion houses will be closely monitoring Williams’s performance at Louis Vuitton.

“Moving forward, I would expect fashion houses to be even more selective and curated with their approach to appointing creative directors. The risks are catastrophic — however, the upside is business-defining,” says Ray. He offers brands some advice. “Focus on the creative value the celebrity can bring, but equally try to create a world in which the brand can also exist outside of the celebrity.” It’s a delicate balance to achieve but one that can bring huge rewards.