Inside an inconspicuous warehouse on the outskirts of north London sit almost 300 years of British decorative history. As you walk through the building, winding past vertiginously high shelving units, neatly stacked with boxes of Cole & Son’s sought-after wallpapers, past the prettily decorated offices papered with walking leopards or fluffy clouds, bold trumpet lilies or the feathery crowns of exotic hoopoe birds, there is a room tucked away at the back of the building filled with a treasure trove of hand-carved printing blocks, some dating back to the 1700s.

The Opening of Cole & Son's Flagship Gallery at Jubilee Place, Chelsea

12th October 2023

Cole & Son’s unique, extensive archive encompasses all aspects of the leading wallpaper brand and offers an invaluable historical resource for the design industry. Here we explore Cole & Son's Flagship Showroom at Jubilee Place that recently opened in September and their decorative archive.

Presented by Cole & Son

“If you had been here six months ago, it wouldn’t have been that nice,” laughs Marie Karlsson, Cole & Son’s charismatic Swedish-born, London-based creative and managing director. “Before this warehouse was also offices, most of the space was used for block printing, which we did here until 2012. They needed to soak the blocks in water for several hours so that the wood didn’t take all the colour during the printing process. The blocks had also been kept in very high humidity, so the smell in here was terrible and they had all swelled.”

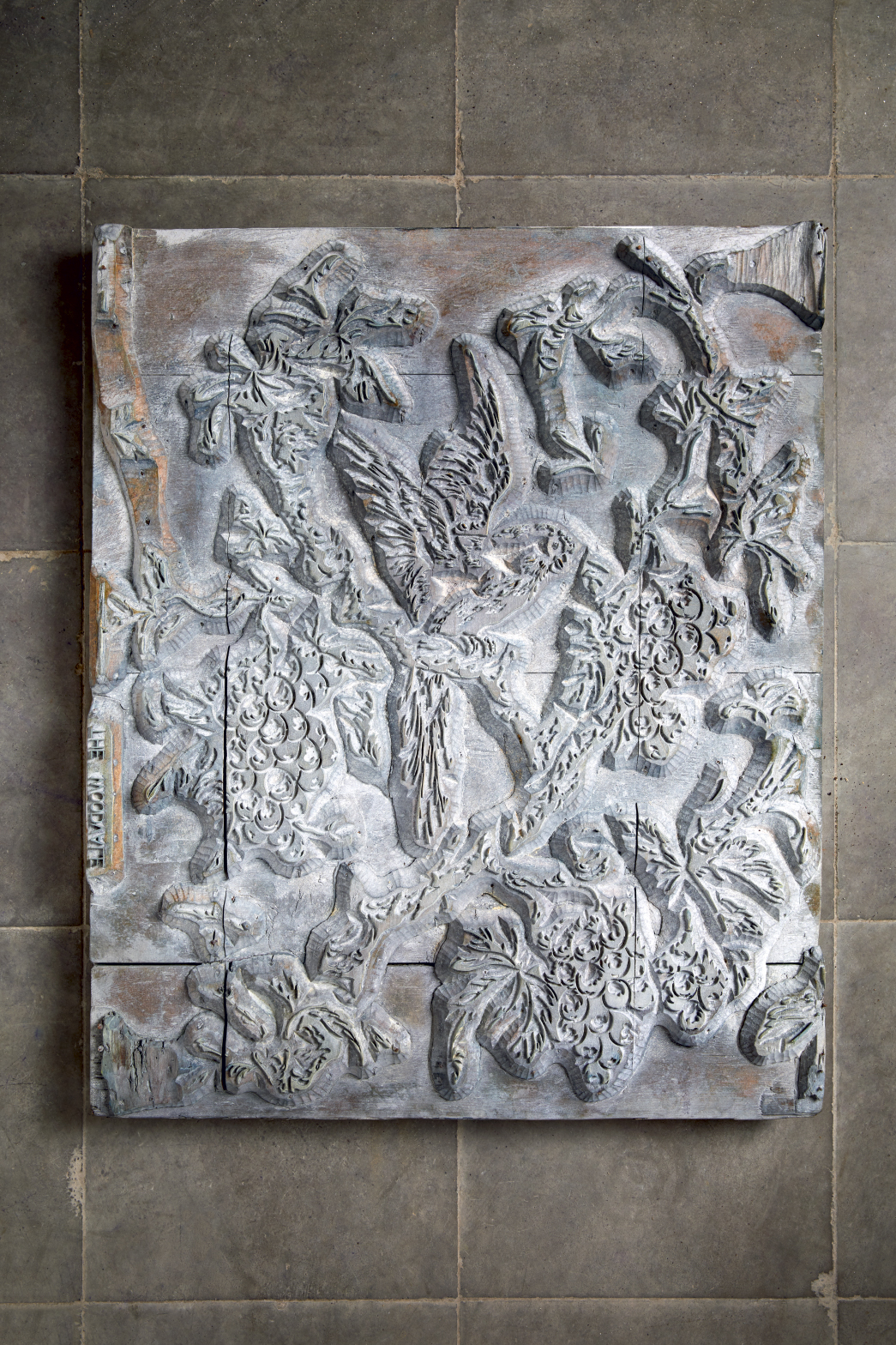

Research into stabilising the blocks revealed they would be just as happy kept dry at a normal temperature, so they were pulled from the water and the heat turned down. “Now they are perfect,” Karlsson says proudly, ushering SPHERE exclusively into the archive where more than 1,500 hand-carved printing blocks are stored in aisle after aisle of metal racks. “Soon we’ll be selecting the best for the VIP room at our new Jubilee Place design house,” she beams.

The 148-year-old British wallpaper company recently opened a new headquarters in Chelsea. “It is the chance to sit everybody under one roof, from the art department to order processing,” Karlsson explains. “I also think it will really resonate with our clients, whether they are an architect, an interior designer or someone from the public, because in this new wallpaper wonderland, we can really share in every step of their interior design journey.”

As well as showcasing the company’s latest designs — and giving customers hands-on help in tailoring designs to suit their needs — the new premises will also offer the perfect historical resource for the design industry. “In our VIP room, people will have access to some of the blocks you see in our archives, a selection of our old logbooks and original artworks, so you can see how all our designs are first hand-painted to scale,” Karlsson says. “Maybe you are a student, an archivist or an artist — you can come to us to see which colours were trendy in the 1890s or which patterns were popular in the 1960s. We want this new space to be somewhere the design community can engage not just with us but also with one another.”

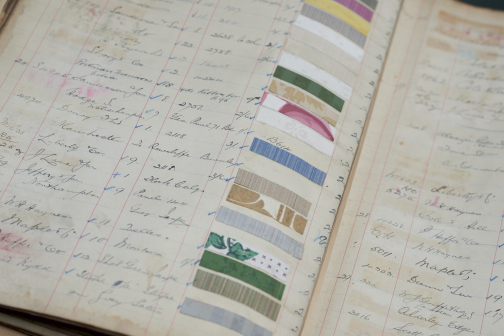

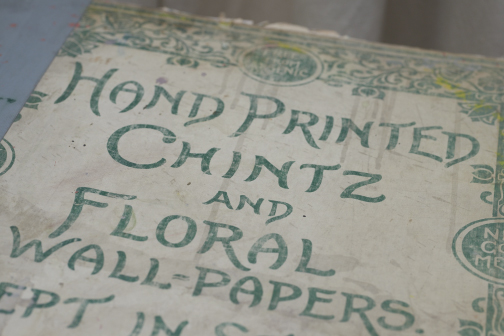

A large part of the Jubilee Place conversation undoubtedly revolves around Cole & Son’s extraordinary archive. Alongside the printing blocks, there are also hundreds of old logbooks that document the details of every wallpaper sold, from the name of the pattern to who bought it and where it went around the world. Other memorabilia includes framed royal warrant stamps and old books of early 19th-century wallpaper collections, standing at waist height. After years of wear and tear, they are dangerously at risk of disintegrating with just one touch. Collectively, this is a fascinating insight into the history of our country’s decorative arts. “Britain has always played such a key role in leading interior design trends, wallpaper is deeply embedded in the genes, in the culture,” Karlsson observes.

This wealth of documentation is, naturally, a constant source of ideas for Cole & Son’s design team. “This is our playground; it is here to give us inspiration,” Karlsson says. Wearing white gloves, she pulls out one block after another. On one there is an intricate blueprint of thin metal strips bending and swirling in a dizzying floral folkloric display. “You can see how this might not only work as a wallpaper, but could also be printed on a cotton poplin or used as an embroidery — or even as the base of a new chinoiserie, or used as a simple monochromatic block print.”

Many of the blocks — stained in faded but alluring shades of rose, tomato red, pistachio and sky blue after centuries of use — tell stories of castles and palaces, grand ballrooms of stately homes and magnificent buildings such as Augustus Pugin’s Houses of Parliament, for which Karlsson pulls out a set of blocks belonging to the Tudor Rose pattern printed for its illustrious walls. Another shows the markings of an 18th-century damask used to inspire the modern-day Balabina pattern (named after the Kirov Ballet ballerina Feya Balabina), which has since been reworked by the design team to include a beautifully drawn bird.

One of Cole & Son’s most popular (and oldest) prints, Hummingbirds, can be seen in a set of blocks where tiny sections of wings and beaks have been hand-carved into one pearwood block (pear is a wood chosen for its malleability as well as its longevity), while the shapes of leaves and twigs are carved into another. “It shows how a design made up of between 23 to 27 colours, created through a combination of wood blocks and hand-painted elements, is built up, layer by layer,” Karlsson explains.

In a more contemporary twist, she pulls out a block designed by John Perry, the company’s founder, that imitates the shimmer of silk. The carvings of the block intimate the sinuous lines of an ordnance survey map, traversing a landscape riven with tall plateaus and deep valleys. The design team are currently using this to develop a modern moiré print, says Karlsson. “It is a very old design for Cole & Son, but we’re changing it slightly by knocking back the structure a little and printing it in powdery hues over different types of metallic to make it really interesting.”

On the mezzanine level of the warehouse, there are racks of rollers, some hand-carved from wood, others made from rubber, all used for surface printing. This method was originally developed during the Industrial Revolution and the unpredictable way the ink transfers to paper lends a hand-blocked feel. Some rollers are still used today, and Cole & Son also draws on myriad other printing techniques, including gravure printing, which allows for “very fine, intricate details and gives a sharpness to a design,” Karlsson says. Screen printing is also used to produce Fornasetti’s monochromatic, surrealist vision of Baroque Rome in the Riflesso pattern.

The new building at Jubilee Place is the perfect space for the Cole & Son team to not only take visitors back in time, but also to help them focus on the present. “It will be exciting to be able to communicate more personally with our customers, to know more about what they love and what they feel might be missing,” says Karlsson. In other industries, such as fashion, purchasers are more open, she notes. “Very few people show their private homes, so we are curious to know how our designs are used behind closed doors. The one thing we do know, however, is that with our heritage and our archive, we have something that nobody else has.”